The Argentines must be the most nocturnal people on the face of the earth. Although this tradition clearly derives from Spain, the Argentines have taken it to a new level. Whereas on the continent, the nocturnal Spaniards will eat around 10 or 11 and begin filling the bars and clubs around 12 or 1, the Argentines eat around midnight and don’t make it to the bars and clubs around 3 AM. You can go out at 8 or 9 and see empty bars. You can pass by around midnight and see them with still just a few loafing foreigners. It’s not until 4 or 5 in the morning do you see them full and bustling with activity both inside and out. The whole city is suddenly alive and scampering with people who came out of the high multi-leveled flats, feeling at last the call of life. As in Spain, you do not really feel the extreme density of the cities until you have experienced the night life. But the night life occurs at such odd hours in Argentina, that you’re better off adapting to it by holding a completely different sleep schedule.

I actually did live with one fellow who was nocturnal. He was a student and I was living in a kind of student boarding house, a noisy, dirty place full of young Argentines and other South Americans. He slept upwards of 18 hours a day and did not stir until dinnertime. The guy was a large, strong, bearlike, bearded type from the south of the country. He’d roll into bed late in the morning, usually when I was getting up after a difficult night of sleep (the constant noise was really taking its toll on my sanity). And he would stay there, snoring quietly, rolling over now and then, until around 10 or 11 at night, just in time to catch a shower before going to eat.

I remember overhearing him at dinner saying that he felt so tired. He rubbed his eyes and brushed his hair back. His eyes were red. His sleeping habit was wreaking havoc on his system. He was becoming more and more tired and lethargic the more he slept. Yet he continued for as long as I lived there. A 20-year old man living like this. He didn’t work or show any real ambition, but he was an excellent classical guitarist. He studied something or other at the university but I never saw him crack a book my whole time there. I don’t even think he went to class. As for partying, I didn’t see him as one to go out very much either. He was mostly sleeping and eating. And when he ate, after just having awoken, he would be yawning the whole time, and in some cases would go straight back to bed after.

Needless to say, he’s not representative of the Argentine nation, just another case in an otherwise nocturnal-leaning country. I remember going out to extravagant meals with my coworkers around 10 or 11 and seeing whole families–mom, pop, grandma and grandpa, the kids, the relatives, etc.–eating together as if it were the most normal thing in the world. Sunday morning around 11 AM, Buenos Aires appears like a city following an Neutron Bomb explosion, in which all the people have died and all the lights are out, but the buildings remain intact. It’s probably the best time to go sight seeing because of this, but can be a bit lonely for the wayfaring tourist.

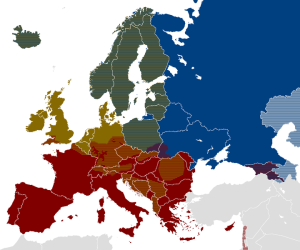

In Spain, however, people don’t really adjust their lives to the weekend rite of going out late; they just bear out the long Friday and Saturday nights and still remain throughout the week on normal European hours. This is of course because they are part of Europe and the EU and must maintain those standard hours of the common market. Since they also want to enjoy their drawn-out Spanish evenings, you see something similar to what happens on Friday and Saturday night, though less pronounced—the streets are mostly empty for a long time, then the restaurants fill up around 10, and the bars shortly afterward. Then the Metro suddenly swarms alive with people, bedecked in their most alluring and provocative clothing. The whole thing sometimes feels like a pagan rite, an ancient tradition stemming all the way back to the Roman era when circenses were partaken with a deep gusto and guiltless pleasure-seeking. I do not know if it this has recurred due to Spain’s sudden lapse in Catholicism and the end of Franco, or if this was something that always was there in Spanish culture, a deep love of the nocturnal pleasures. Whatever the case, it all happens like clockwork and doesn’t seem to depend on the weather, the economy, or the weekend. Whenever and wherever, the cities will fill to the brim with life on Friday and Saturday night, but only after 10 o’clock.

Although I say this is indeed pleasure seeking behavior as if that were a bad thing, I have to add that in many respects it’s more civilized than what you see in the Anglo or northern European countries. In Spain and Argentina, the night is long and slow. People do not drink until their head hangs over the toilet bowl, starting at 8 and passing out by 2. They start sipping a light beer or glass of wine, and spend most of their meal time chatting loudly. Then they enjoy a few more drinks sprinkled with more food and then go out dancing. Conversation rarely turns frank and philosophical, as it does among Anglos and other Europeans, and things rarely take a dark turn into drugs or fighting. The conversation and flow remains light at all times; there is a surprising lack of conflict and restraint, although the conversational style often comes off as argumentative. (The way to talk in Spain is for everyone to yell at once and the loudest person to be heard. If you want to order something you have to go up and be the loudest person to talk and ask in the most direct way imaginable. Otherwise, you’ll never get any service. I think this is a Mediterranean trait and can come off as crass to outsiders, but you have to understand that it’s normal to them and they don’t think they’re coming off as harsh.)

Also, there aren’t as many different subgroupings in Spain and Argentina: fewer Goth clubs, or hip-hop clubs, or rock-only pubs, etc. There’s a homogeneity to the culture, which leads to a generic bar and club style: the bars are for eating over beer and chatting while listening to pop and the clubs are more for drinking harder alcohol and mixed drinks while listening to techno and some more trendy American pop. So people tend to follow the same trends and there is less of a sense that people only go to one type of pub, club, or other venue and only listen to one type of music. Less variety, to be sure, but less isolation as well.

Lastly, I’ll add that in all this night life, random coupling “hooking up” doesn’t occur–believe it or not–as often as you’d suspect. Women and men do show off and dress up, but they are out to have fun, not to find a one-night stand. Your chances are much better with the women of northern Europe if that’s what you seek. There are a few reasons for this. Usually Spaniards and Argentines go out in self-contained groups that do not associated with other people. They may encounter friends and join with them, but they do not usually venture to meet strangers. And the groups can be rather large, so it although may look like autonomous people, but they are usually there together. Because of this, all the old social pressures apply (which are greater in these less individualistic countries) and especially since people aren’t plastering themselves with booze, random coupling remains rare. Of course, there’s a lot of flirtatiousness and showing off but in general going out is just a way to pass the time and socialize. The social circle is an impediment and hurdle that must be circumvented or encountered if you’re to have any luck. Generally speaking, you need to get to know people and their groups of friends to be accepted and then go on a date with someone. This may be changing, of course, but that was my experience and observation.